1. At the time, my girlfriend and I were staying at a two-month rental high up in the Sta. Ana hills, a one-bedroom : the second storey of a gable-roofed family home, up a clanking metal staircase : an afterthought of a spiral affixed to its side. The first night, lying in bed, I heard the canine howl — hollow in the distance — of somebody's pet through the open window and hushed, unfamiliar streets, and I cried thinking of my own Stella back home, far below and miles away.

3. Here, the role of the Creature is shared between two different digimon — the infected Diaboromon in "4 Years Later" and the re-infected Kokomon in "Present Day.” Willis, an elementaryschool-age computer whiz, plays the part of Viktor. Being from Summer Memory, Colorado, he’s on the other side of the world, in a state of total physical isolation, from the rest of the cast in Tokyo. ( It’s probably not a coincidence that NORAD, both in real-life and as represented in WarGames, is located in rural Colorado. ) Even more, throughout his appearances in “8YA” and “4YL,” we never see Willis in the same frame as another person, nor does he seem to have any plans to be, exacerbating this sense of separation. His Digital Monsters being his only irl-friends, out of a want for companionship ( a feeling fans of virtual pet franchises should have no problem empathizing with ), he creates his own in Diaboromon.

It's worth noting that Pokémon : The First Movie — Mewtwo Strikes Back, released two years before, features its own riff on Frankenstein, with its title Monster created by another lonely scientist Dr. Fuji, arising from a desire to steal his child from death.

4. Wong himself on the influence of literature in Chungking Express's narration : “Haruki Murakami was very popular in Hong Kong then, and because Kaneshiro Takeshi is half Japanese, I thought it would be funny to have his voice-overs written in Murakami style.” And while we're at it, I might as well mention that Chungking — an eccentrically bipartite film — and Fallen Angels were originally imagined as the same movie : a threeparter omnibus, likenable to how Digimon : The Movie ended up.

”d-d-digimon”

. . .in the company of endings.

file_01 : bg-layer.djvu

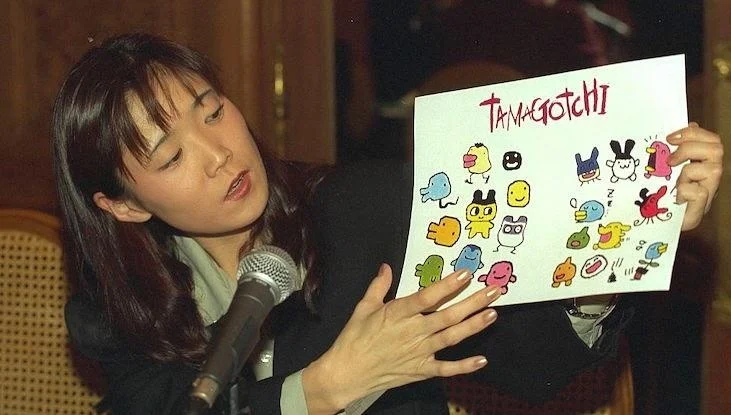

Digimon has always had the weak heart of a copycat. And even more so than Pokéfans typically allege. After all, it began not as the anime series it’s most well known for, but as a 1997 line of v-pets produced by Bandai following the proven success of their Tamagotchi the year prior — itself based on Japanese "aquarium fish simulation software" of the early '90s. But Pokémon showed itself of far greater pecuniary import, so Bandai couldn’t just doze on their laurels. Hence now with Digimon : Digital Monster your 16x16 pixel pets can duke it out with friends', a design-concept lifted straight from their competitor. For his own part Pokémon's creator Satoshi Tajiri famously borrowed

Digimon has always had the weak heart of a copycat. And even more so than Pokéfans typically allege. After all, it began not as the anime series it’s most well known for, but as a 1997 line of v-pets produced by Bandai following the proven success of their Tamagotchi the year prior — itself based on Japanese "aquarium fish simulation software" of the early '90s. But Pokémon showed itself of far greater pecuniary import, so Bandai couldn’t just doze on their laurels. Hence now with Digimon : Digital Monster your 16x16 pixel pets can duke it out with friends', a design-concept lifted straight from their competitor. For his own part Pokémon's creator Satoshi Tajiri famously borrowed inspiration from his childhood hobby of bugcollecting blended, I suspect, with an ancient cultural inheritance surrounding bugfighting across the Sinosphere. Not to mention the iconic pokéball seems a sci-fi re-vision of the gashapon capsule — the term gashapon being a trademark of Bandai.

inspiration from his childhood hobby of bugcollecting blended, I suspect, with an ancient cultural inheritance surrounding bugfighting across the Sinosphere. Not to mention the iconic pokéball seems a sci-fi re-vision of the gashapon capsule — the term gashapon being a trademark of Bandai.

Digimon's inclusion of a battlemode leads many to describe Digimon as Tamagotchi for boys. I say, if that’s what they were going for, then they sure did a bad job of catering to the stereotyped demographic : I mean, a central feature of the progression in Digimon is picking up their droppings ; in Digimon World ( 1999 ) for PS1, this mechanic developed into pottytraining. On top of that, the only appropriate response to the network-y sophistication of the many digivolutionary futures that might be in store for your babies — all hinging on the quality of your care choices — is to hover and worry and fuss. This design-decision, inherited from Tamagotchi, is contrapuntally opposed to the linear spirit of PKMN : just muscle your way through battles and the kids’ll be alright. Yes, the childrearing sim of it all extends well beyond Pokémon’s aim and desmene.

So despite whatever masculine intention Bandai supposedly had, Digimon ended up bringing a fresh androgyny to this field of kids' electronics, polarizing the concept of the datapet in both directions at once. Further, from the very start creature designs drew from varied styles and sources to the point of collage, incoherence, and humor. Viktor Frankenstein — an infertile guy with a desire to, despite the barrenness of his sex, create — would be proud of Bandai’s prolific knife- and stitchwork, the vivifying switch of their microelectronics, and the monsters thereby they made and gifted strange, miraculous animacy.

file_02 : digi.mov

“But then where are your friends tonight ?”— "All My Friends," LCD Soundsystem

One night1 I came across a review from someone claiming to have watched the Digimon movie “500 times easy. . . seeing it at the cinema at like 3 years old then watching the vhs every day after kinder until it broke.” It’s not at all hard to imagine. And while my own personal viewcount hasn’t even broken the single digits, after reading that, I felt I’d found someone who understood me. Probably there were parts of me they understood better than I did — it only seemed logical. So, on Fri 11/11/2022 at 9:32 PM, I shot out an email, with the slight hope of befriending them, ending it thus :

From a certain perspective, you must be one of the foremost experts on this film on the entire planet. Has that thought crossed your mind ? It crossed mine instantly upon reading your review. I myself have talked for hours and hours about this film, trying ( tirelessly ) to tease out its tangled ideas and atmospheres. It would be super cool to talk to you about it sometime ! Please write back if you ever get the chance — no hard feelings if you don’t. After all, what's a few raindrops between fans ? :)A good 16 months have passed since that night and : no dice. Oh well. I guess another thing you could say for the movie’s quality is I‘d base a whole friendship on it if I could.

What about the film itself ? Well, to start with, there are fights between giant beasts right out of kaiju cinema. And — like in Godzilla ( 1954 - 2024 ) — when, in the first section ( “8 Years Ago” ), our ally Greymon takes on Birdramon, all jagged ungues and fire, the spawn of a hugeradiused egg that fell from the sky with zero forewarning, there is something of the atomic age in it. Unlike the two other antagonizing Digital Monsters to come, no reason is ever given for Birdramon’s sudden, devastating appearance, lending a sheen of the absurd to the engagement. Why is there such destruction in the world ? is a question never asked, much less given an answer.

And then in the next section ( “4 Years Later” ) there's a nuclear scenario with clear parallels to WarGames ( 1983 ) ; this time around, though, we’ve got the Y2K bug scare baked into it — yep, we’ve gone from bugfighting. . . to bugfighting. WG is a fully admitted influence : before it got absorbed into Digimon : The Movie ( 2000 ), “4YL” was a Japan-only short film literally subtitled Bokura no Wō Gēmu ! ( 2000 ), or "Our War Game."2 The last two sections of Digimon : The Movie — "4YL," which we just touched on, and “Present Day” — can be read together as a convoluted retelling of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein3, the blueprint for so many Monster stories. This movie does not just happen to contain but is in its very DNA a laundrylist of popculture quotation.

All together, there’s two seasons’ worth of main cast ( 11 humans + 11 partnermons ) to keep track of as they filter in and out of a stiched-up, timehopping triptych of narratives, each of which possesses its own art style and protag re-designs. Through it all, digimon change forms, voices, even names, often quite inexplicably.

How could this all possibly come together ? the uninitiated might ask reading this, understandably concerned. Well, to be totally honest, it doesn’t. But you’re so wrapped up in the thrilling spectacle — you’re having way too much fun to care.

And you’re not alone. This isn’t The Sacrifice ( 1986 ), it’s Etat Libre D’Orange’s La Fin Du Monde, with its “ironic blast of pop-corn accord.” In "4YL" awestruck spectators from across the worldwide web look upon the highstakes battle metaphorically. They are us, invested just as much and as little as we are. No crowds are seen to mass or shout in panicked streets. For some strange reason, outside of entranced 'net spectators and our combatants, people seem to just to get on with their lives : attending birthday parties, taking exams, preparing snacks while cracking jokes. There’s a curious nonchalance to the end of the world.

Why is that ?

There’s a secret. You can feel it burgeoning, gathering force and shape. Now that it’s all over. Under layers of popculture pastiche, jukebox soundtrack perfection, expertly paced action, words of unending hope and humor — under the pleasure of your confusion, it burns. The secret is : this is a meditation on the paradox of love in absence of the ones you love. Of love in the company of endings. And when I say secret, I mean Rae and I didn’t realize it until having seen it several times ; and Hen didn’t get that from it at all until I gave a little exegesis on our postviewing walk. Remember : all the letters, bright with color, saying a hundred times what Joe never once says, left at Mimi's door, many spilling out the mailslot ? The sparely worded Haiwaii postcard we see she sends not to him, but to Tai. And what did it say, really ? Only that she isn't here. And remember : all the phone calls Tai makes. How many of them ever reached their target ? How many wishes fell on the floor to crack like a glass vase ? Failing to reach Mimi, Joe, TK, Matt, Sora — especially Sora — in the time he needs them most, Tai lies defeated on the floor of his apartment, or drapes his body over the couch, and bemoans life. The moment passes : everything does. It’s not lingered over : nothing is.

Oh, it all happens in the background, Hen summarized in a quiet voice as we paced through the night and the maze of his subdivision, nerves stimulated by the cool air, burning off Korean corndogs. In the background : the way mourning happens for someone without the time or patience to mourn. They are kids.

“That’s the saddest story I’ve ever heard,” Davis sobs.

“I’m the one with the problem, not you. Get over it,” Willis replies.

“Okay.” And he does, beaming.

It’s executed with all the abrupt comedy of a Peanuts strip, and hides the same tender belly of wounded reflection.

One way love-in-absence comes through in Digimon : The Movie is the pattern I've just laid out : intentions toward love that go nowhere. And where desire has no place to land, i.e., where it becomes useless, surplus, we're made to appreciate the feeling itself. There are a number of different structures of broken-off desires we're shown.

Given that D:TM is, fundamentally, a hasty patchwork of previously extant material thrown together at the last minute out of fear of having nothing to wear to the party Pokémon started with its first couple multi-milliondollar blockbusters, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that there’s a distinct sense of the disjunct haunting the whole enterprise. The plot structure is not one anyone would make — for a kid's movie — on purpose. So a 1st-person narrator gets thrown into the mix as a kind of sticky glue to bind the three disparate segments of film together. Which sounds like a sensible choice given the circumstances, I guess. Pokémon has a narrator : some abstract announcerman recapitulating previous episodes to whoever happens to be tuning in.

But it's not the same, not really : the speaking voice here is Kari's, her lines colored by want and thought. It's actually more similar to the technique you see in the comparably disjoint films of Wong Kar-wai — e.g. Chungking Express ( 1994 ) and Fallen Angels ( 1995 ) — and the effect is much the same here : a sense of anachronistic sentimentality more literary than cinematic4, matching the eclectic, slapdash energy of the work.

One of the stranger moments to come out of this arrangement occurs in the final moments of "8YA." At the tail-end of the first kaiju showdown, children we've never met are shown staring down from high windows or balconies on Hikarigaoka5. Somehow, no one else in Tokyo pays any mind but the DigiDestined, who are not seen to cheer nor cry but, in an unexpectedly soporific manner, watch, stand, wait.

It's the way Nerima looks that really drives the feeling home. Olivia Laing writes of New York, New York : “The city reveals itself as a set of cells, a hundred thousand windows, some darkened and some flooded with green or white or golden light. . . [S]trangers [in their] private hours. You can see them, but you can't reach them, and so this commonplace urban phenomenon, available in any city of the world on any night, conveys to even the most social a tremor of loneliness, its uneasy combination of separation and exposure."

When the fight is won and dawn breaks on the ruined city, Kari's voice prophesies : "That night changed our lives. It was awhile before we realized that those who saw it became the DigiDestined." But like — I reiterate — at this particular moment, they're total strangers to us and will not so much as meet Kari for another 4 years.

When I think about my friends, about the times before we knew each other, sometimes I get this sense of missed connection too. You know, the way people sometimes say, "If we met back in highschool, we would totally have been friends," and then they playfully fictionalize how it might've happened. But when you think about it a second too long, isn't that so odd ? Because being that person's friend is a desire you feel now ; it’s not one you could’ve known without knowing ( of ) them. So impossible desire makes a migratory flight to the scene of the past from the future. This feels so natural, so real, and a bit painful : to create a void that was not there before.

Gaps & Doubles

"If only we could've met earlier” must be the rarer mirror to "Why did ever we part ?”6 — in both cases, we are wanting for more time together than life has apportioned us, unwilling to accept the distance the present entails. We step through just this mirror seconds after Kari's narratorial line, arriving "4 Years Later" in the post-Adventure atomization that colors the film's remainder ; and so we are left to hallucinate for ourselves the halcyon days between the first and second parts. Their most treasured togetherness is revealed only as something pined for at both ends. The Adventure kids' once-deeper friendship existing purely through this kind of emotional implicature is the first of a number of lacunæ, or suggestive gaps in the narrative, that break off desire, and put the absence in love-in-absence.

Another concerns Tai Kamiya, the headband-and-goggles protag of pts. 1 and 2, who up and disappears from the lengthy final chapter. This creates an unsatisfied yearning on the part of fans and viewers, rather than the characters themselves, who — weirdly — are silent on the matter.

The last lacuna belongs to Willis : in pt. 3 the 02 kids all want to see him, but it just keeps not happening for one reason or another, and once they are finally met, and he with great pains earns their companionship, it is deep, but of a temporary sort. After the film ends, we know he will return to the same isolation of his home, an ocean away from all his friends, "starting [his] separate days."7

But as in Chungking Express, absence is not only absence but speaks also through the figure of the double, the replacement, the doppelgänger. In "8YA" Tai and Kari raise an Agumon, but soon after it banishes Birdramon from Tokyo, the Agu absconds, never to be seen again. Then "4 Years Later," Tai, with no explanation, has a new partner-Agu, with a wholly unfamiliar voice and personality. I already noted Tai's marked absence from "Present Day" ; but the franchise doesn't abandon him without providing a serviceable replacement. Kari even says it to us : "Yeah, I know Davis looks a lot like my brother Tai. They even have the same personality: obnoxious!" a line clearly admitting a double. But even if she hadn't told us this, we'd figure it out. I mean, he's got pilot's goggles worn not over his eyes but above them, spiky hair, leaderstatus, skatervoice. . .

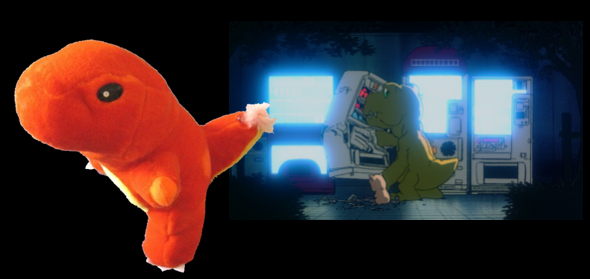

Last, and most significantly, let's talk about Willis's Kokomon(s). In "Present Day,” the only segment where Willis is not at the extreme periphery of the narrative’s attention, Kokomon, who has been Willis’s friend since near-infancy, is re-infected by the very same virus Diaboromon had. His prognosis is just as bleak too. After they return to the site of his conception, Summer Memory, consisting of a single dirt road, a couple roadside telephone booths, billboards, and the vast emptiness of the Interior Plains, bright with permanent sunlight, they kill him.

"Don't be sad, Willis. One thing you have to learn about Digimon, they never really die," Davis opines, dwarfed by the vacancy of dreamy pasture and blue cliffs that contains them all.

"Huh ?" is all Willis can manage before he's in New York, New York, saying parting words.

In the next and last scene, he's ambling along a littoral road accompanied by Terriermon, his sole remaining partner, whereupon a DigiEgg comes bobbing in on the tide and washes ashore. "He also found out that Davis was right. Digimon never really die. Their information just gets reconfigured, only sometimes they come back singing a different tune," Kari puts in from some unglimpsable future. People who aren't Willis sure have a whole lot to say about his personal understanding of datapet theology. To be fair, Willis, seeing the hatchling, does indeed call his dead pet's name with a tone of excited recognition that suggests reunion. But there's a profound identifactory trouble in this. And the full extent of what Willis has to say for his new partner, as he sways and moans along to "All Star" in an irritating closeup, is, "He's tone deaf." Which isn't exactly an encouraging final line.

These doubles are not fantastic, but imperfect likenesses, recruited out of the pain of loneliness that another bestows by distance or death and memory. On the one hand, such resemblers fill-in for what is lost, but they also continually retrieve our loss, remind us of it. And reminders like these can be painful in their own right.

Could I submit that, maybe, besides making you feel bittersweet things, this preoccupation with doubling is self-conscious in nature ? That the multivocal attitude on the reincarnation of the digital soul the film puts forward in its last moments is a sort of wincing, hesitant reflection of the franchise's own unoriginal origins — or even an attempt at vindication ? In this light, we might regard the Digimon movie as a kind of metempsychotic art, as empty and as lovely as the souls in transmigration.

A Brief Apologia Before We Stitch This Thing Up

In thinking about any apparently lighthearted property in a grim manner, in taking on children's media with a youngadult's earnestness, there is always the fear of missing the point ; but, at least here, I don’t think that pertains. Digimon : The Movie comes at a moment in the franchise right before Chiaki Konaka — writer of Serial Experiments Lain ( 1998 ) — takes the reigns for season three : Tamers ( 2001 ), the acme of Digimon edge. Which is not to say, The right eye to have to this film is a monotonously gloomy one. But rather I believe the cœur of our movie lies in a disorientingly contradictory mode that mixes the jocose with the melancholy, the sincere with the glib.

file_03 : reflect.exe

I love fanfic. I love a good unlicensed plush that’s got the dimensions all wrong and looks a little wonky. I also love Warhol’s Monroes and Tomato Soups and fakedesigner. I have a penchant for the knockoff that probably says less about me than the spirit of the times. That probably says less about zeitgeist than selfnature. Is this making sense yet ? Like Mullholand Dr ( 2001 ) after it and Annie Hall ( 1977 ) before it, the Digimon movie we end up with is nothing like what it once thought it was. Instead, it is a film that was forced to adapt to the weird chaos of its idiot birth, burning off first-intentions like ghost money. The consequence ? A work as disorderly and capricious as life. “Around 700 years ago, particularly among the Japanese nobility, understanding emptiness and imperfection was honored as tantamount to the first step to satori or enlightenment.” What if what we reach for using words like virtue, destiny, and love is largely indifferent to our own private longings, to ego ? What then ?

The Digimon Movie stumbled into existence with reluctance, under the weight of obvious inferiority and selfhatred. There, there, weakheart : sometimes, the shitty reproduction glows with the same vivid edges as the homespun. Weakheart — there, there : I love you more than any other art I’ve ever known.

— Ivy, 03.16.2024

2. The original WG is very much a product of the United States Cold War : a sort of Action / Comedy starring Matthew Broderick and Ally Sheedy — the guy from Ferris Buehler’s Day Off ( 1986 ) and the vaguely goth girl from The Breakfast Club ( 1989 ), both younger, not-yet-charismatic, playing a classically meager ‘80s nerd hero and his bland love-interest. Its subject : the anxiety of annihilation by nuclear arms. Of course it goes without saying that, for Japan, such annihilation was not only anxiety, it happened, to two major urban centers. With this in mind, it’s no wonder WarGames was chosen to tell again anew : to make Theirs. ( In “4YL” Diaboromon launches precisely two nuclear missiles originating, in a reversal of the 2001 attack of the coming year, from "the Pentagon's computer." )

It's telling that the Armageddon WarGames envisions arrives on the wings of mistaken innocence : a teen plays what he reasonably assumes is just some silly computer game, only to find out it’s actually a sophisticated Artificial Intelligence program belonging to NORAD and capable of untellable destruction. Similarly, the most significant humans-vs.-AI flick of the period, The Terminator ( 1984 ), featuring the future governor of California Arnold Schwarzenegger in his careerdefining role, lays its Hellish future at the feet of another totally well-intentioned genius : one Dr. Miles Benett Dyson who creates Skynet, and so indirectly also the title Monster. Again, for NORAD. By means of a paranoid flavor of Science Fiction, both films envision a world where we no longer have to worry about the Soviets or any foreign power anymore for that matter. Instead audiences can widen their eyes at the immensity of the horror our Defense Command is capable of inflicting on its own people via cybertronic innovations. The whole structure, win or lose — and we always win — gives a hint of treacly nobility to the imagined downfall, like a kitschy poem about The Titanic. Yes, these are nightmares exhibiting a deep fear of their own country’s destructive carelessness, but they are nightmares that bend entirely inward, alternating between egocentric self-reproach and power fantasy. What looks so much like techno-military-beauracratic doom can be overcome by an exceptional individual through sheer force — The Terminator — or raw, slacker-intelligence — WarGames. Sure, there’s a latent guilty conscience, an apocalyptic masochism behind these films. But, through it all, not an outward glance is cast, for even a second, to the nondomestic victims that such weapons systems are really designed to obliterate — so unlike “Our War Game” / “4YL.”

5. Hikarigaoka is the main street nearest where Toei Animation made Digimon at the time. You may also find it slightly interesting to know that, only 2 months after the release of Digimon : The Movie, Toei began operations on their Toei Ōedo Line, “the most expensive subway line ever built,” which Hikarigaoka Station sits at the end of.

6. A lyric from "All Of My Everythings" off the Promise Ring's Very Emergency ( 1999 )

7. Ibid.