STRAYS

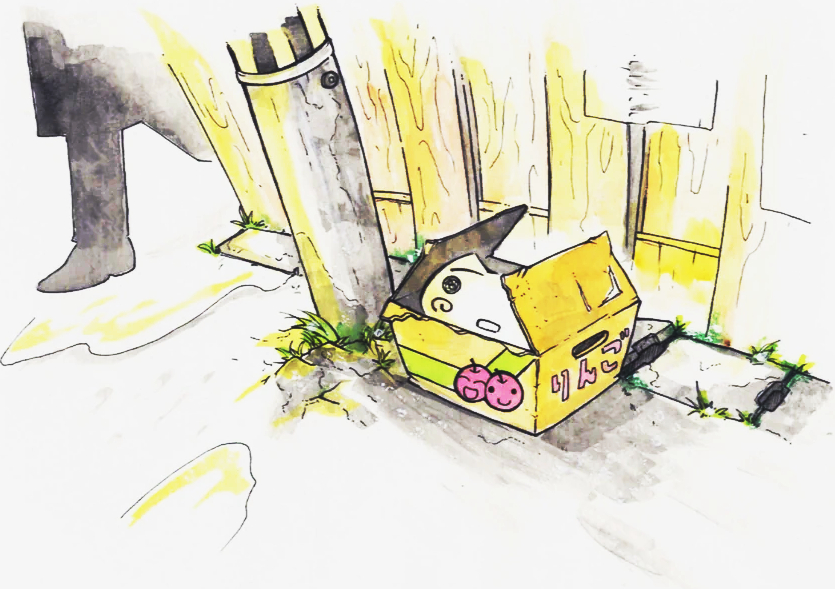

It looks like someone discarded their thought in a shabby cardboard box. How careless.

It’s sure making a lot of noise. You’re not one to have any peculiar abilities, and definitely not whatever supernatural aptitude lets psionics converse with animals — I mean, hear other people’s thoughts. But you listen closely anyway. . .

It looks like someone discarded their thought in a shabby cardboard box. How careless.

It’s sure making a lot of noise. You’re not one to have any peculiar abilities, and definitely not whatever supernatural aptitude lets psionics converse with animals — I mean, hear other people’s thoughts. But you listen closely anyway. . .

— Take me somewhere safe, it says. But where ?

There’s a sign winking high above the overpass : Shelter for Stray Thoughts : a star that burns all night long.

The first thing I know about myself is that I made my mother very sick. I have been told this dozens of times over the years, mostly by my father as he wears that strained smile of his that at once keeps me at a distance from and endears me to him : when she was pregnant with me, she always had to vomit. I am never quite sure what to say to this. I feel pity, but is this really a situation where I can offer an apology ? That seems akin to apologizing for being born. ( This is one of the more troubling ambiguities in the English language : the collapse of sorry as an expression of sympathy into one of contrition. Even more troubling is how hard it is to tease apart those ideas in my own soul. ) Similarly, the next thing I know is that during my first plane ride I was unable to be pacified, shrieking nonstop from liftoff to landing.

When I talk about all this, I can’t help but feel a twinge of embarrassment. Really it’s a fear that somebody, on finding out I was a difficult baby, will be upset with me. It’s one of those things that sounds ridiculous when you say it out loud but is granted a strange plausibility as an unexpressed fear.

The first moment of my life that properly belongs to me — and not someone else’s recollection or glossy 4x6 or magnetic tape — is a memory of visiting a store. This was in Hawaii, near a beachfront ( paved ), and the spray dashed itself on the rocks like unicorns against some endless cheval de frise. I browsed the aisles until I came to an endcap hung with little toy soft animals, from which I took a gecko, red with zigzags all over. My parents bought it for me and over the years, as I became a pre-teen, and then a teenager, and then a full-fledged adult, I almost threw it away many times, but a surreal sense that to do so would be defying fate forbade me to.

My second memory is of a little shop in an airport ( this part can’t be right, but I can’t remember it any other way. . . ) with rows and rows of jewel cases sitting on little platforms hung from the wall. My eye was caught by the art for a game I now recognize as Digimon World 3 : brightgreen code rushed toward me from a vanishing point occluded by a trio of 3D-rendered Digital Monsters slightly fanned out and overlapping one another like a hand of trading cards. I asked my father for the game but did not receive it ; I have still never played it.

It’s hard to think very objectively about my parents’ genitalia. As an adult I find it upsetting to recall in new ways, which makes it difficult to understand exactly how I felt as a child about it. I remember getting into the shower with my mother as my father was just getting out. It’s fair to say it wasn’t pleasant, that I felt confused and fearful seeing their naked bodies. I couldn’t imagine growing up and having a body like either one of them. It just seemed strange, like suddenly realizing my parents were aliens, and gave me a vague but intense feeling of trepidation.